This episode explores unintentional weight loss, its potential causes, and the diagnostic approach to uncover underlying medical or psychiatric conditions. It emphasizes the importance of targeted history, physical exams, and basic tests in patient evaluation.

Transcript

[00:00] Hello and welcome back once again to Surgery 101. The podcast series brought to you with the help of the Department of Surgery at the University of Alberta. I’m Dr Jonathan White. Coming to you live from the Royal Ag Center

[00:20] Hospital in Edmonton. This is the latest episode in our series of episodes on general surgery. This week we’ll be hearing again from Dr. Leah Gramlich, my gastroenterology colleague here from New Orleans, Alexandria, about the topic of unexplained weight loss. And this is one of those topics that I’m afraid to say we don’t teach very well in medical school, because it’s a fairly general

[00:40] presentation and it’s not necessarily connected with any one particular system. So Leah will be exploring the topic for us. She’ll be defining what is significant in terms of weight loss. She’ll be explaining what happens when you lose weight and what are some of the possible causes and she’ll be describing an approach to trying to figure out what’s happening in a patient who’s had a significant

[01:00] significant amount of unintentional weight loss. So let’s get ready to investigate the case of the missing weight here on Surgery 101.

[01:20] Welcome. My name is Leah Gramlich. I’m a gastroenterologist and a physician nutrition specialist and on this surgery podcast today I’m going to talk to you about approach to the patient with unexplained weight loss. There are four learning objectives in this talk.

[01:40] The first is to describe significant weight loss, to discuss the impact of unintentional weight loss, to talk about the causes of unintentional weight loss, and to describe an approach to the patient with unexplained weight loss.

[02:00] Weight loss is a very common problem seen by generalists whether they’re in family medicine, surgery, or in internal medicine. Patients who are overweight or obese may intentionally lose weight to improve their health. However, progressive weight loss

[02:20] without trying or involuntary weight loss often indicates a serious medical or psychiatric illness. We’re going to discuss an approach to unintentional weight loss in the adult patient. Let’s start with a definition. Unintentional weight loss is also referred to as involuntary or unintended weight loss. I refer to it as

[02:40] non-volitional weight loss. This term excludes weight loss as an expected consequence of treatment, for instance weight loss from diuretic therapy with heart failure or weight loss following bariatric surgery or as a result of known illness. Clinically important weight loss is often defined as a weight loss of more than 5% of usual weight over

[03:00] 6 to 12 months. Involuntary weight loss of 5% to 10% of weight is potentially significant, and involuntary weight loss of over 10% of usual weight is always of consequence. The strongest independent predictors of unintentional weight loss include age, smoking, and poor self-reaction.

[03:20] health. And the prevalence of unintended weight loss increases with age and is also higher amongst those with obesity, a group that’s particularly difficult to nail down the diagnosis in. Although there are many causes of unintentional weight loss

[03:40] At a basic level, there are four key mechanisms. The first is reduction in nutrient intake. The second is increased energy utilization, such as in the case of fever or hyperthyroidism. The third cause is increased loss of

[04:00] that might be from malabsorption or short bowel syndrome. And the fourth cause is altered metabolism. In the absence of fever or other causes for increased energy expenditure such as hyperthyroidism, in fact, weight loss is predominantly in

[04:20] usually do to reduction in food intake, and you’ve got to elicit that on history. Progressive unintentional weight loss often indicates a serious medical or psychiatric illness. Any chronic illness affecting any organ system can cause anorexia and weight loss. In studies that looked at ueology

[04:40] for unintentional weight loss, cancer is eventually identified as the primary cause in 15 to 35% of patients. Non-malignant GI causes count for about 10 to 20% of patients. Psychiatric causes account for 10 to 23% of patients. And in a quarter of cases, we don’t understand the cause.

[05:00] Cancer is particularly of the lung, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and prostate often cause weight loss and there are multiple mechanisms including anorexia and reduction in poor intake. The prevalence of weight loss is highest in

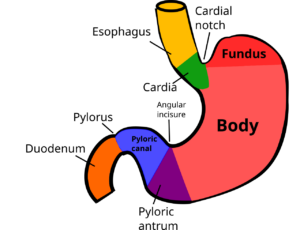

[05:20] those with really complex cancers. Non-malignant GI tract diseases such as pepidoculcer disease, celiac, inflammatory bowel disease can also present with weight loss. And these patients often have GI symptoms including abdominal pain, early satiety, dysphasia, or oodinephasia, diarrhea,

[05:40] or stioderia. They might even have evidence of chronic bleeding. In patients with psychiatric disorders, depression in particular accounts for weight loss in a third to almost two-thirds of patients with unintentional weight loss. This is more prominent

[06:00] in nursing home patients and seniors. Eating disorders and other conditions such as bipolar may also contribute to weight loss in patients with psychiatric disorders. Endocrinopathies such as hyperthyroidism and diabetes contribute to altered nutrition

[06:20] metabolism and both of these conditions can be associated with weight loss. Another condition we need to consider in patients who present with weight loss is adrenal insufficiency, although clearly this is less common. Infectious diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis C, and chronic halmuthic infections can also

[06:40] contribute to non-volitional weight loss. Another area of medicine where we see non-volitional weight loss is in patients with advanced chronic diseases such as chronic cardiac, lung, or renal disease. Intercurrent illness in patients with chronic illness can also impact non-volitional weight loss.

[07:00] As physicians, we also must consider social factors leading to inadequate dietary intake, such as food insecurity or the absence of enough money to buy food and wheat. Athletes who have excessive energy expenditure may also present with weight loss.

[07:20] So how do we evaluate patients with nonvolitional weight loss? Given the broad differential diagnosis of unintentional weight loss, there’s no single diagnostic approach for patients. And although many patients complain of weight loss, this might not be documented. The workup of the patient with unintentional weight

[07:40] needs to be individualized and be based on findings from the patient’s history and physical. The examination should start with verifying weight loss with a targeted history and physical examination. The Subjective Global Assessment is a reliable and valid tool to use for assessing nutrition status and nutrition risk in patients

[08:00] patients who claim to have lost weight. History should focus on weight loss, the amount, the pace, the timing, amount of oral intake, the presence of GI symptoms, the functional status of the patient, and the stress of the condition for which they’re presenting. Physical examination should focus on evidence of lean tissue

[08:20] Best identified where there is loss of bulk in tone in major muscle areas such as the deltoids or the gluteus maximus muscles. And you also want to look for fat loss in the intercostal spaces and in the triceps. You can also look for edema. Physical exam

[08:40] should also pay attention to head and neck looking for adenopathy, cardiopulmonary exam looking for evidence of COPD and cardiac decompensation, abdominal examination looking for masses, and a cognitive and neurologic evaluation.

[09:00] cup. Four unintentional weight loss is based on the findings from physical and history. When the history and physical examination don’t indicate a likely diagnosis, basic diagnostic testing can yield a diagnosis in the majority of cases, and subsequent testing depends on the initial test. A basic diagnostic evaluation should include

[09:20] complete blood count, electrolytes, vioin, and creatinine, glucose and hemoglobin A1c, thyroid testing with TSH, liver function tests, occult blood testing with stool, and consideration for hepatitis C serology and HIV serology as indicated. Subsequently, if a

[09:40] clear cause for weight loss is not found and no abnormality is identified, watchful waiting for anywhere from 1 to 6 months is preferable to a battery of tests with low diagnostic yield. On follow-up, careful attention needs to be paid to dietary history, possibility of psychosocial causes, surreptitious drug intake, and new manifestations of occult disease.

[10:00] Patients with progressive weight loss that’s documented over multiple visits versus stabilized weight loss should be seen in a shorter timeframe. Further evaluation for cancer in older patients may be reasonable. In summary, clinically

[10:20] important weight loss is traditionally defined as a weight loss of more than 5% of usual body weight over 6 to 12 months. Weight loss of 5 to 10% is potentially significant and certainly weight loss of over 10% of usual body weight is always significant. Mortality rates are increased when weight loss is unintended.

[10:40] There are many causes of unintentional weight loss and it often indicates serious underlying medical or psychiatric illness. There is no single diagnostic approach for all patients, but the evaluation should start with verifying weight loss, targeting a history and physical

[11:00] exam and then using a workup with a battery of blood tests to identify likely culprits. Thank you.

[11:20] Thanks once again Leah for this excellent podcast and thanks for covering such an important topic which is sometimes not taught quite so well in our medical schools. Next week we’re changing it up with a little bit more general surgery this time in the colorectal area. We’ll be looking at the topic of rectal examination and perianal abscess.

[11:40] So thanks for listening and we look forward to seeing you back here next week on Surgery 101.