This episode dives into glaucoma, focusing on its types, symptoms, and management. Learn about open-angle glaucoma, acute angle closure glaucoma, and surgical and medical treatments to prevent vision loss.

Transcript

00:00] Hello and welcome back to Surgery 101. The podcast brought to you with the help of the Department of Surgery at the University of Alberta. My name is Jonathan White and I’m a surgeon here at the Royal Alex

[00:20] Sandra Hospital in Edmonton. This week’s episode is the second in a series of five episodes all about the eye, brought to us by medical student Kim Papp. Last week we covered the basic structure and function of the eye. This week we get to feast our eyes on the topic of blood coma. We’ll be looking at the

[00:40] of the condition, the different sorts that there are and the different treatment options. So let’s get ready to think about what happens when you’ve got a little bit too much pressure in your eye here on surgery 101.

[01:00] Glaucoma. Welcome to this episode of Surgery 101 on glaucoma, where we will learn the basics of this common ocular disease. My name is Kim and I am a fourth year medical student at the University of

[01:20] Alberta. I’d like to give a huge thanks to Dr. Chris Rudniski for his expert review of this content. Today’s objectives are to 1. Describe the eye anatomy relevant to glaucoma. 2. Understand the pathophysiology, symptoms, and management options for open-angle glaucoma. 3.

[01:40] Understand the pathophysiology, symptoms, and management options for acute angle closure glaucoma and, four, list other causes of glaucoma. Definition. Glaucoma is a common eye disease. In glaucoma, patients get optic nerve damage. Glaucoma is associated with

[02:00] high eye pressure inside the eye called intraocular pressure, or IOP. Not all cases of glaucoma have high IOP, but it is safe enough for this introductory discussion to think of glaucoma as optic nerve damage with elevated intraocular pressure. The

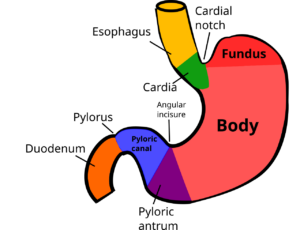

[02:20] The cutoff measurement for high IOP is usually 21 millimeters of mercury. Anatomy. How can you even get high pressure inside the eye? To understand this, we need to discuss aqueous humor and the angle of the anterior chamber. Aqueous humor is the

[02:40] that fills up the anterior chamber, which is the space between the cornea and the iris. Aqueous humor is constantly being produced and drained out of the eye, so IOP can rise if aqueous is not being drained effectively. The ciliary body,

[03:00] behind the iris produces aqueous humor. You may know that the ciliary body’s second job is to anchor the zonules that suspend the lens. Let’s follow the path of aqueous humor in the eye. The ciliary body produces aqueous from here, aqueous flows in

[03:20] front of the lens, forward through the pupil, and into the anterior chamber. From there, aqueous drains into the angle formed by the cornea and the iris into a drainage system called the trabecular meshwork. From the trabecular meshwork, aqueous makes its way into the venous

[03:40] system of the body. As an aside, if you are loving this discussion of eye anatomy and physiology, check out our other Surgery 101 podcast episode on eye fundamentals. Open-angle glaucoma. In North America, by far the most common type of glaucoma is open

[04:00] open angle glaucoma. This is the type that is screened for at optometry eye exams. You may have experienced the unpleasant puff of air onto your eye when you were looking at the hot air balloon picture. This is one way to measure eye pressure, or IOP. We screen for open angle glaucoma, OAG,

[04:20] because most patients with OAG are asymptomatic and because OAG causes gradual vision loss if we don’t intervene with management. What do we mean by open angle? Remember that the angle that we’re talking about here is the angle in the anterior chamber between the core

[04:40] Here, aqueous humor drains into the trabecular meshwork. In open-angle glaucoma, the angle is perfectly normal and not too narrow, so the reason for the high IOP isn’t that the drainage angle is closed. So if the angle is

[05:00] fine in OAG, what’s causing the high intraocular pressure? The thought here is that with age, there is microscopic dysfunction or clogging of the trabecular meshwork. So in open-angle glaucoma, aqueous humor can’t drain effectively through the trabecular meshwork.

[05:20] which raises IOP and damages the optic nerve. The three major findings of chronic open-angle glaucoma are 1. high IOP, 2. optic disc changes, and 3. visual field loss. Let’s break each of these down

[05:40] before diving into treatment. As mentioned before, the cutoff for high intraocular pressure is an IOP greater than 21 millimeters of mercury. For optic disc changes, ophthalmologists train to notice subtle changes in the appearance of the optic disc that signify

[06:00] damage from glaucoma. One of these is a cup to disc ratio greater than 0.5. The details of this cup to disc ratio are beyond this introductory episode. For visual fields, patients with OAG tend to lose their peripheral vision slowly over time.

[06:20] This is why we check their visual fields. To do this, ask the patient to look at your nose and hold out your hands midway between the two of you, holding up either one, two, or five fingers, and ask the patient how many fingers they count. Make sure they’re always looking at your nose and not taking a peek.

[06:40] off to the side where your hands are. You can assess how well they see in each quadrant of vision with each eye. Let’s look at management of open-ingle glaucoma. There are many medical treatment options in the form of eye drops that are first line. These include topical prostaglandin and

[07:00] beta blockers, alpha agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Since this podcast is with Surgery 101, however, we will focus our discussion on understanding some surgical treatment options for OAG, which usually come after trials of eye drops.

[07:20] It’s fairly simple to remember the two main surgical approaches for glaucoma. The issue is that aqueous humor builds up inside the eye, elevating IOP. So, one approach is to decrease production of aqueous, another is to increase drainage of aqueous.

[07:40] Do you remember which structure produces aqueous humor? The ciliary body. We can surgically laser the ciliary body so that it produces less aqueous humor, which lowers eye pressure. Laser destruction of the ciliary body is not often used to treat glaucoma because once the ciliary

[08:00] body is destroyed, there’s no way to turn the tap of aqueous humor production back on. The main method to reduce production rather than surgery is with topical medications or drops. Do you remember where the eye drains aqueous humor? The trabecular meshwork. Apart from medications,

[08:20] there are a couple of surgical ways to tackle this, trabeculectomy or trabeculoplasty. A trabeculectomy is a surgery to create a new drainage path separate from the existing trabecular meshwork. The surgeon cuts a tiny hole at the superior limbus where the cornea meets

[08:40] the sclera superiorly. Aqueous humor now drains through that trabeculectomy hole under the clear conjunctiva tissue. An alternative to creating a hole is placing a tube at the same site that drains aqueous into a fixed plate under the conjunctiva. So those were trabeculectomy

[09:00] A second approach is known as a trabeculoplasty, or SLT, where we laser the existing trabecular meshwork to open it up and improve drainage. SLT laser has been shown to be the best initial treatment for open-angle glaucoma. So that is a

[09:20] whirlwind tour of open-angle glaucoma. In short, this is chronic high IOP from trabecular meshwork dysfunction that damages the optic nerve and causes gradual peripheral visual field loss. We usually start with medical eye drop management, but later surgical

[09:40] options include increasing outflow using a laser or surgery, or decreasing aqueous humor production at the ciliary body. Closed angle glaucoma. We need to discuss acute closed angle glaucoma as another type of glaucoma, as this is a medical emergency

[10:00] that can result in permanent vision loss. Remember how with open-angle glaucoma, the angle between the cornea and the iris was open and normal? The problem was instead with the trabecular meshwork. In angle closure glaucoma, the problem is that the angle is too narrow and this is why aqueous canons

[10:20] drain properly. How does the angle get narrow anyway? The most common mechanism is by something called pupillary block. If the lens somehow ends up touching the back of the iris, aqueous tumor can no longer flow in front of the lens and through the pupil. This block in front

[10:40] fluid movement creates a pressure gradient that effectively sucks the iris and the lens forward, which closes the angle between cornea and iris so aqueous cannot drain out. So how does the lens come to touch the pupil? Most commonly it’s because cataracts develop in every

[11:00] The lens gets physically larger as you age, and this takes up space in the eye, narrowing the angle. Patients with angle closure glaucoma present acutely unwell, nausea and vomiting their holding their hand over their painful eye. On exam, you’ll see a sluggy

[11:20] mid dilated pupil and you’ll measure an IOP that is very high. Most emergency rooms carry a tonopenne which measures eye pressure. Be careful because these can be inaccurate if used incorrectly. One common mistake is that tonopenne users might accidentally

[11:40] press their finger on the patient’s eyeball while measuring IOP, which falsely elevates the pressure reading. If you need support for your hand while using the tonopad, rest your hand on the patient’s bony orbit around the eye, not on the eyeball itself. Patients with acute angle closure glaucoma

[12:00] should see ophthalmology right away to avoid permanent vision loss. Again, this is an emergency. To treat this, we often use the kitchen sink approach of giving many eye drops, such as a beta blocker, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, a myotic, which constricts the pupil, and intravenous mannitol.

[12:20] Patients with angle closure glaucoma require a hole lasered into their iris called an iridotomy. This hole relieves the pressure gradient so that the iris isn’t pushed forward anymore and the angle reopens. Ultimately, patients who have a cataract will need their cataract removed.

[12:40] to make more space between the iris and the cornea. Other types of glaucoma. We’ve discussed the two types of glaucoma that new learners should definitely know about. Open angle glaucoma and acute angle closure glaucoma. But we want to include some honorable mentions as there are some other causes of

[13:00] glaucoma to be aware of. Neovascular glaucoma happens because of abnormal new blood vessel growth from diseases like diabetes. In early stages, this acts like an open-angle glaucoma with some fibrous tissue growing over the angle. In later stages, however, this

[13:20] could become an acute angle closure glaucoma if the abnormal blood vessels pull the iris forward, causing a closed angle. Check out our Surgery 101 podcast episode on diabetic retinopathy to learn more about diabetes and the eye. Another cause of glaucoma is pigment dispersion.